Toward a Concrete Utopia Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948ã¢â‚¬â€œ1980 Review

Toward a Physical Utopia: Compages in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980, Museum of Modern Art, New York, July fifteen, 2018 –January, xiii 2019

New York'southward Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) recently provided a stage for a vital – and very much on-trend – test of the brutalist, socialist architecture of the former Yugoslavia, exhibited nether the title Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980. Structured around a set up of thematic and biographical sequences, this momentous survey of socialist architecture brought together more than 400 drawings, models, photographs and video installations from a wide range of individual and institutional athenaeum across the former Yugoslavia and across. In showcasing Yugoslavia's socialist architecture as a defined and singled-out phenomenon, Toward a Concrete Utopia makes an argument for compages's chapters to produce a shared sense of history and identity inside a highly various, multiethnic order.

The history of Yugoslav socialist architecture has to date largely been absent from the discipline'southward canon. Equally exhibition curators Vladimir Kulić and Martino Stierli argue in the accompanying catalog, architectural history has repeatedly failed to offer a proper evaluation of the achievements of this region, attributable largely to a strong Western-centric bias entrenched both by Cold War soapbox and the Orientalist positioning of the region every bit Europe's "Other". (Martino Stierli and Vladimir Kulić, "Introduction," Toward a Concrete Utopia: Compages in Yugoslavia 1948-1980 (New York: The Museum of Mod Fine art, 2018), p. 7.)

In seeking to address this situation, the curatorial duo saddled themselves with the ambitious task of documenting the accomplishments – and global attain – of Yugoslav socialist compages and, in so doing, remapping the history of modern compages.

The assembled works span the period between 1948, which marked a formal split betwixt Yugoslavia and the Soviet bloc, and the decease of long-fourth dimension Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980. These were three decades of dynamic transformation, during which the land was able to successfully establish a unique international identity. In seeking to distinguish their own brand of socialism from that of the Soviet Matrimony, Yugoslav leaders decentralized the economy and introduced a model of self-management, liberalized cultural and artistic life, and positioned the country as equidistant from the 2 Cold War superpowers by condign a founding fellow member of the Not-Aligned Movement in 1961. This "tertiary way" would prove to be a position of privilege during the Cold State of war: after the death of Joseph Stalin and normalization of relations with the Soviet Marriage in 1955, Yugoslavia was able to piece of work with both Eastward and West – eating, every bit one EU diplomat would afterward describe information technology, "from both sides of the banquet table."(Aida Hozić, "It Happened Elsewhere. Remembering 1989 in the Former Yugoslavia," in Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubic eds., Twenty Years Subsequently Communism, Oxford Scholarship Online, 2014, p. 30.) While maintaining this international position was a fine balancing deed, so was the procedure of managing the country'due south complex internal dynamics. Founded under the slogan "brotherhood and unity," Yugoslavia was a multinational federation held together past the notion that the national and the supranational could operate in concert inside a socialist framework. With Tito's decease in 1980, the story goes, the fragile ideological structure underpinning this slogan would – like so much of the exhibition'south titular concrete – quickly brainstorm to crumble.

The exhibition endeavors to capture the complex dynamic between collective and private regional identities, and in doing so makes a strong case for Yugoslav compages as a conceptually rounded exercise grounded in this dynamic. This argument is underscored by the exhibition's rhythmic transition between private and collective, national and socialist, local and global. Emphasising this signal, each of the 4 thematic sections – Modernization, Global Networks, Everyday Life and Identities – is interspersed with profiles of architects who either contributed to a specific area of compages or had particular regional significance.

Towards a Concrete Utopia opens with the theme of modernization, as a series of post-Earth War II reconstruction pieces call attention to the incredible speed with which Yugoslavia transformed from an agrarian to an industrialized and urbanized club. The scope of this drive is captured at every level, from large-scale projects such as the Belgrade Master Plan (1949-50) or the South Adriatic Regional Program (1968), to a series of individual museum, university and library buildings, sport and recreation facilities, hospitals, kindergartens and international fairgrounds – collectively the institutional infrastructure that supported the building of socialist life in Yugoslavia. Here the curators remind us that all identities are constructed – some in reinforced concrete.

Urban Planning Institute of Belgrade, Belgrade Main Programme, 1949–50, Belgrade, Serbia, Programme one:10000, 1951.

Inside this opening section, Andrija Mutnjaković's project for the National and University Library of Kosovo in Priština (1971-82) is a showstopper. The central element of the then newly-established Academy of Priština, this structure captures the spirit of socialist life-edifice every bit a force of emancipation and education, while honoring the local context past incorporating elements drawn from both Orthodox Christian and Muslim tradition. Cubic volumes and domes are repeated in a seemingly endless sequence, with aluminium filigree reminiscent of local craftsmanship roofing the unabridged façade and lending a sense of coherence to the overall pattern. Mutnjaković'south edifice plays particularly well against an adjacent model for the Museum of Contemporary Fine art in Belgrade (1959) whose architects, Ivan Antić and Ivanka Raspopović, opted for a rhythmic repetition of six interconnected cubes. Though an imposing structure, the articulate and restrained lines of this building (which has itself just re-opened, following a painstaking, decade-long restoration project) fuse harmoniously with the surrounding landscape. Founded by painter and fine art critic Miodrag B. Protić after his visit to New York (and specifically to MoMA) in 1962, the Museum represented a clear indicate of the aspirations of the young country and its capital.

Andrija Mutnjaković, National and University Library of Kosovo, 1971–82. Priština, Kosovo. Exterior view. Photograph: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016.

The fact that identity is both synthetic and performed is underlined in Mila Turajlić's video piece We Build the State – The Country Builds Us! (2018). In assembling a series of clips from Yugoslav films and newsreels that focus on the operation of labor, Turajlić accentuates the centrality of the shared experience of the postal service-War reconstruction of Yugoslavia. Broad-spread (ostensibly voluntary) participation in then-called work deportment (radne akcije) brought together people from all corners of the country, with the bonds formed through this shared effort serving every bit both the literal and metaphorical foundations for the new socialist country.

Mila Turajlić, "Mi gradimo zemlju – zemlja grad nas/We build the country – the land builds us!" 2018. Three-aqueduct video. Installation view of Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, The Museum of Modernistic Art, New York, July 15, 2018–Jan 13, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Martin Seck.

The ensuing section of the exhibition is dedicated to global networks, with Yugoslavia and its cities showcased as international hubs of activeness and exchange. The reconstruction of Skopje following a devastating convulsion in 1963 is a prominent – and arguably the well-nigh captivating – feature here. With some 80 pct of the Macedonian capital letter having been destroyed, in 1964 the United Nations ran an international contest for a new master plan for Skopje; Japanese architect Kenzō Tange claimed victory, and with it an opportunity for Japanese architects to engage in a massive international project for the start fourth dimension since World State of war II. While some elements were left unexecuted, many of those that were built would come to be recognized as paradigmatic examples of Yugoslav socialist architecture and its brutalist aesthetic. The Macedonian Opera and Ballet (1968-81), designed by a group of architects known as Biro 71, is a clear stand up out hither, with its clangorous construction and white-coated physical appearing to ascent majestically from the surrounding landscape in a dynamic upward dive.

A small-scale section dedicated to Belgrade-based construction visitor Energoprojekt examines another global trajectory, as socialist Yugoslavia during this fourth dimension served also as a major exporter of architectural and building expertise. The country'southward prominent position within the Not-Aligned Motility helped to forge an expansive network of economic and political ties, primarily to newly independent countries throughout Africa and Center East, and Yugoslav enterprises institute themselves with numerous opportunities to work on major development projects. In tracing the story of Energoprojekt's global accomplish (and especially the firm'south work in Nigeria), the exhibition focuses on Belgrade architect Milica Šterić – the offset prominent Yugoslav female person architect and founder of Energoprojekt's compages branch – who held leading roles within this enterprise both as an architect and also as a manager, designer and mentor. This story provides an opportunity to contemplate the common emancipatory impulse underpinning Yugoslav socialism and the contemporaneous processes of decolonisation that were at this time unfolding beyond the globe.

A survey of the tourist center architecture concludes this story of global connectivity. Images of hotels and resorts sourced from the archives of Turistkomerc – a Zagreb-based enterprise charged with promotion of Yugoslav tourist destinations – are here displayed on a looping slideshow reminiscent of holiday photos being displayed in a family living room (accompanied by blow-by-accident commentary). This intimate and nostalgic atmosphere cleverly sets the tone for the following department, which is defended to Yugoslav everyday life.

Hither telephones, radios and folding chairs that filled and then many Yugoslav homes are displayed adjacent stellar examples of Yugoslav mass-housing architecture, such every bit Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić's edifice cake Split iii (1970-79). Some other video slice by Turajlić entitled Living Space/Loving Infinite (2018) suitably frames this space, with its collage of clips from iconic Yugoslav films that foreground the familiar (and romantic) dramas unfolding within these apartment blocks. While so many discussions of socialist housing compages habitually focus on either its brutalist aesthetic or the anti-social behaviour associated with (or rather provoked by) life within these physical mazes, the curatorial team here foregrounds a different dimension of this compages – namely its highly experimental nature. Indeed, this is a red thread that runs throughout the exhibition: whether focus is trained on the design of a large-scale slice of public infrastructure, an opera firm, a hotel, a mass-housing projection or a monument, the spirit of experimentation is presented as a defining characteristic of this socialist architecture.

Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić. Braće Borozan building cake in Split 3. 1970–79. Split up, Croatia. Exterior view. Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Fine art, 2016.

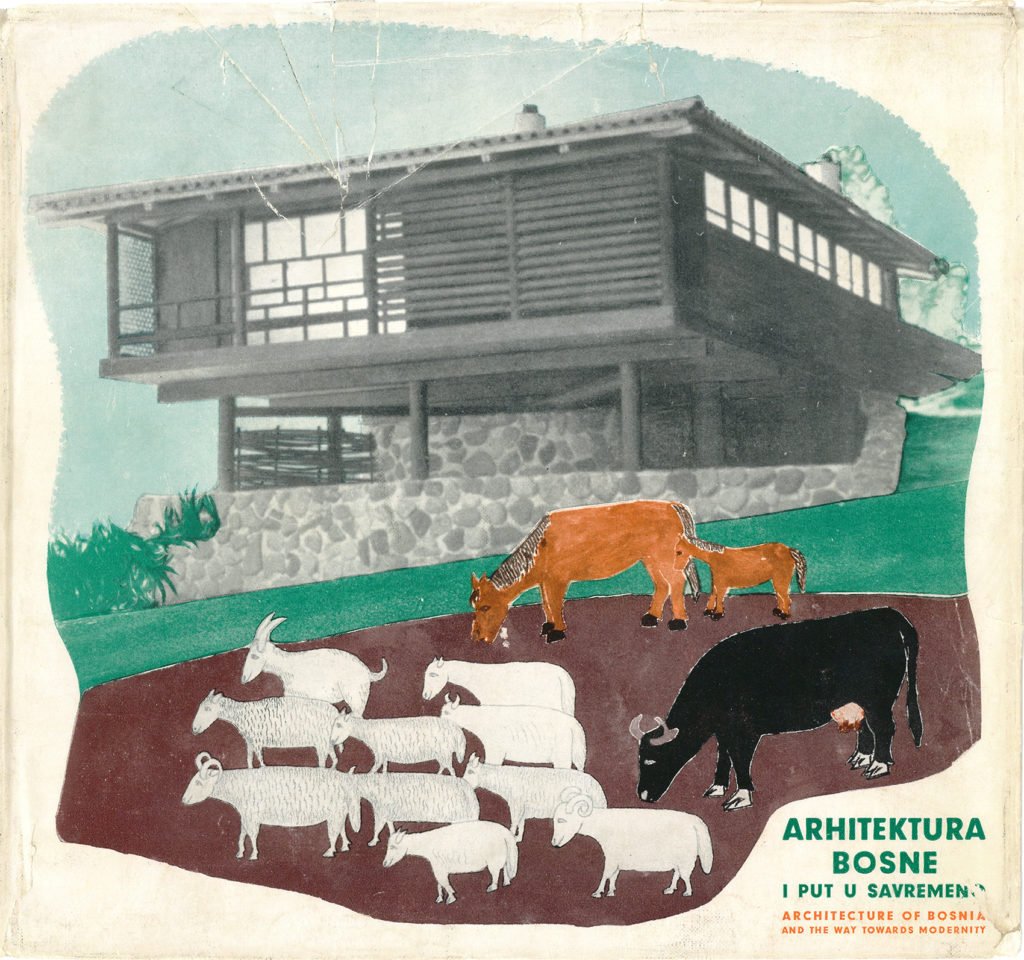

The last sections examine identities and are primarily organized around the profile architects Edvard Ravnakar, Juarj Neidhardt and Bogdan Bogdanović. As a federation of six republics and ii democratic provinces, Yugoslavia was a patchwork of different cultural identities and historical traditions; in the works displayed in this section, modernism serves equally the framework through which architects sought to forge unity within this multiplicity. A display of drawings and illustrations from Neidhardt's study Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity (1957) is a special highlight. Born in Zagreb, Neidhardt would eventually settle in Sarajevo where, in collaboration with his Slovenian colleague Dušan Grabrijan, he worked to produce this volume, in which he argued that Bosnia'southward traditional architectural vernacular – its whitewashed walls, abstract cubic volumes, built-in furniture and large windows among others – was already in essence modernist, and could therefore serve as the basis for articulating the modern Yugoslavian architectural idiom. Intriguingly, these ideas echo concepts first developed by Yugoslavia's interwar avant-garde, and primarily the Zenitist movement (1921-1926), whose members argued that the Balkan creative impulse – with its iconoclastic and irreverent bent and predilection for the idiosyncratic – was modernist avant la lettre and therefore an ideal basis for a new and progressive Yugoslav identity.

Dušan Grabrijan and Juraj Neidhardt, Embrace of Architecture of Bosnia and the Way to Modernity, 1957. Private annal of Juraj Neidhardt.

The exhibition culminates with a striking exam of memorial architecture, featuring predominantly those monuments that were created to honor the victims of World State of war II. During the war, communist-led partisan forces fought not just against the fascist enemy, just also against a range of nationalist military groups that operated across the land. As ane of the European countries that suffered the highest casualty rates, the wartime experience defined Yugoslavia equally a country forged from the enormous cede of its people. The state of war became a critical part of the country's founding myth, creating a common sense of belonging to this victorious narrative was meant to heal divisions along national and indigenous lines. Accordingly, an examination on the piece of work of Bogdan Bogdanović, who dominated the field of memorial architecture, grounds this section, which centers around a display of the plans for Bogdanović'southward near well-known projects, including the Belgrade Monument to the Jewish Victims of Fascism (1951-52), the Jasenovac Memorial Site (1959-66), and the Shrine to the Fallen Serb and Albanian Partisans in Mitrovica (1960-73).

Sketches by Bogdan Bogdanović. Installation view of Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 15, 2018–January xiii, 2019. © 2018 The Museum of Modern Fine art. Photo: Martin Seck.

Bogdanović's interest in ethnography and Surrealist fine art, and his focus on the coaction between structure and the surrounding landscape underpin what is a unique rendering of memorial architecture, positioned equidistant from both the contemporary abstractionism and the socialist realism that had otherwise dominated this field. Indeed, the diversity and the experimental nature of Yugoslav memorial architecture is strongly represented throughout this section, with Miodrag Živković's Monument to the Boxing of the Sutjeska (1965-71), which commemorated a crucial partisan wartime victory, and Iskra and Hashemite kingdom of jordan Grabul's Monument to the Ilinden Uprising in Kruševo (1970-73), capturing attention as outstanding examples of the genre.

Miodrag Živković, Monument to the Battle of the Sutjeska, 1965–71, Tjentište, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, 2016.

Jordan and Iskra Grabul, Monument to the Ilinden Uprising, 1970–73. Kruševo, Macedonia. Photo: Valentin Jeck, commissioned by The Museum of Modern Fine art, 2016.

Toward a Concrete Utopia does an excellent task of presenting a coherent story of Yugoslav socialist compages in its full scale – from master plans to folding chairs – and within a global context that reaches from Nigeria to Japan. Every bit a story, even so, the exhibition has some bullheaded spots. The conclusion to include architectural projects for Cosmic cathedrals in Mostar and Podgorica and a mosque in Visoko without whatsoever reflection on the presence of religious architecture in a socialist country seems unusual. In addition, if i of the curatorial goals was to document the history of Yugoslav architecture, insight into the difficulties encountered in realizing the exhibition – which was assembled in a context in which successor regimes beyond the former Yugoslavia treat the socialist by with suspicion, and where efforts to preserve Yugoslav-era documentation have been undermined both past the wars of the 1990s and the privatization of state-owned enterprises – would surely take been telling. Ultimately, of course, only so much tin can be fit into a single exhibition.

Finally, a note on the choice for exhibition championship: Toward a Concrete Utopia does non avoid the securely-entrenched habit of associating any artistic (or other) endeavour stemming from the socialist Eastward with utopianism, which is a common feature of both bookish and curatorial practice. The term utopia is often used without any theoretical consideration and applied simply equally a synonym for something impossible and impractical – a beautiful dream that could never be – and therefore an endeavor doomed to failure. By applying this label, whatsoever notion that the world could be radically reimagined is cast into the realm of fantasy. In their essay for the exhibition catalog, all the same, Stierli and Kulić foreground an alternative definition of utopia – one grounded in a long philosophical tradition that differentiates between utopias that are indeed impractical and impossible from those that are grounded in reality and, while possibly not realizable at the moment in time, take indeed a time to come potential for realization. Hither they draw upon the work of philosopher Ernst Bloch who indeed insisted on the difference betwixt "abstract" utopias – those that are fundamentally unrealizable – and a "concrete" utopia, which contains a futurity possibility and which the exhibition championship playfully refers to.(Stierli and Kulić, "Introduction," Toward a Physical Utopia, p. 8; Ernst Bloch, The Principle of Hope, vols. 1-3 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996, esp. 142-47.)

The conceptual shift that Stierli and Kulić make is of import, equally it represents a concerted effort to truly remap the history of this region. In contrast to the habitual labelling of socialist art (and architecture) as appealing but impractical, the curators insist that despite Yugoslavia'due south failure every bit a political projection, the ideas that underpin its architecture – architecture that serves the common skillful and celebrates an emancipatory drive – should not be dismissed as wishful thinking, because a radical reimagining of reality was, and is, possible.

Source: https://artmargins.com/toward-a-concrete-utopia/

0 Response to "Toward a Concrete Utopia Architecture in Yugoslavia 1948ã¢â‚¬â€œ1980 Review"

Post a Comment